The United States military has been a superpower for many years. Heroism is attributed to all of the service members in the armed forces. Many American citizens have shaped the history of this country and do not receive the credit they deserve.

Unfortunately, many US citizens don’t fully realize the diversity of American military veterans. There are numerous minority groups that proudly served in the United States military even before its integration in the mid-20th century. Like all members of the military, they wanted to show their patriotism and pride for their home.

Minority military units served in all major wars before WWII. The United States military was desegregated in 1948 when President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which required the “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.”

The ‘Tuskegee Airmen’ Flew Combat Missions With Distinction In WWII

The Tuskegee Airmen were African American military members who served the United States. The regiment was created in 1939 and was active through 1945. Historically Black colleges and universities implemented Civilian Pilot Training Programs in 1939 because Congress was afraid that war would break out. The Tuskegee Institute had been founded by Booker T. Washington. It is estimated that 1,000 pilots were trained at Tuskegee from 1941-1946.

The 332nd Fighter Group consisted of four fighter squadrons: the 99th, the 100th, the 301st, and the 302nd. The US Army Air Corps (AAC) sanctioned the training of Black airmen at Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) in Alabama. They flew over 15,000 missions during WWII.

In addition to training pilots, the Tuskegee Institute trained over 14,000 other military support personnel. The airmen of the 99th served in North Africa and Italy. The airmen of the 100th, the 301st, and the 302nd served in Italy. African American airmen also served in the 477th Bombardment Group formed in 1944. All told, the Tuskegee Airmen were responsible for destroying over 260 enemy aircraft. There was a myth during the war that they never lost a bomber, but this was later debunked. Still, they had one of the lowest loss rates during WWII.

The Tuskegee Airmen faced racial segregation when they returned home. Their response to the problem – including nonviolent civil disobedience – anticipated Truman’s integration of the military in 1948, and provided inspiration for the civil rights movement of the following decades.

Pilots of the 332nd won the first United States Air Force fighter gunnery competition in 1949. The official record listed the winner that year as unknown until 1995, when Harry T. Stewart Jr. – who participated in the competition – began doing some research. The trophy from the competition was finally found at the United States Air Force Museum.

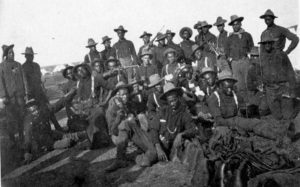

The Buffalo Soldiers Served In The American West And Battled Native Americans

The Buffalo Soldiers were African American soldiers in the late 19th century. They made up the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments – all-Black regiments led by white officers. Three Black officers did graduate from West Point and hold leadership positions: Henry O. Flipper, John Hanks Alexander, and Charles Young.

Predominantly stationed in the American West, the Buffalo Soldiers built roads, worked in the national parks, and promoted Westward expansion. They fought in the Indian Wars, Red River War, and the Battle of San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American War. Eighteen Buffalo Soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their role in conflicts against Indigenous peoples from 1870-1890.

There are two theories as to how the Buffalo Soldiers got their name. First, it was suggested they were named after their dark, curly hair, which people in the 19th century thought looked like buffalo hair. The second theory is that they were so named because of their fighting ability – they were tough, like the Great Plains buffalo. Additionally, the soldiers often wore coats made out of buffalo hides to keep warm in the winter.

The Buffalo Soldiers had opportunities to buy property, access to higher education, and better jobs than many Black Americans of the era. Still, despite their military service, many faced racism. Some were even victims of lynching, which made it painfully clear to many African American servicemen that their service had not made them equal citizens.

Within Weeks Of Emancipation, Black Soldiers Were Enlisting In The Union Army

The Second Confiscation and Militia Act of July 17, 1862, allowed President Lincoln to employ African Americans in his army. President Lincoln did not allow African Americans to fight in combat until after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation stated:

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

Ms. Budge Weidman, a National Archives volunteer, compiled a comprehensive list of all the African American units that fought in the Civil War. She found that African American units from Louisiana served in the war as early as 1862.

The most famous USCT (United States Colored Troops) regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, was mustered in early 1863 and commanded by a white officer, Col. Robert Gould Shaw. The regiment’s actions – including an ill-fated attack at Battery Wagner, dramatized in the film Glory – demonstrated the combat effectiveness and esprit de corps of Black soldiers.

In May 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was established to organize soldiers from all across the country. After the establishment of this bureau, the African American units were referred to as USCT. The state regiments and Corps d’Afrique in the Department of the Gulf were slowly integrated into the USCT.

A number of USCT units were attached to General William T. Sherman’s army. Sherman disliked African American soldiers and purposely left them behind on his 1864 campaign through Georgia. Sherman placed General George Thomas in charge of a racially diverse group of 55,000 soldiers. Thomas, tasked with guarding Tennessee, thought the Black soldiers were not fit for combat, but he was proven wrong when USCT soldiers performed valiantly at the Battle of Nashville, where the Confederate Army of Tennessee was routed and driven off the field in confusion. In the Eastern theater, USCT troops were heavily engaged at the disastrous Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg.

More than 180,000 Black soldiers served in the Union military. By the end of the Civil War, there were 87 African American officers in the Union Army.

Confederate Black Units Were Mustered In 1865 As A Last-Ditch Effort To Stave Off The Union

The Confederate Army mustered African American units in March 1865. They did this reluctantly as a last-ditch effort to beat the growing Union armies, but it was too little, too late.

The previous year, one of the Confederate field commanders, Patrick R. Cleburne, had suggested to Joseph E. Johnston that they arm the enslaved men of the South to fight in the Confederate Army, and emancipate them as a reward for their service. Cleburne wrote in a letter to Joseph E. Johnston dated January 2, 1864:

The immediate effect of the emancipation and enrollment of negroes on the military strength of the South would be: To enable us to have armies numerically superior to those of the North, and a reserve of any size we might think necessary; to enable us to take the offensive, move forward, and forage on the enemy. It would open to us in prospective another and almost untouched source of supply, and furnish us with the means of preventing temporary disaster, and carrying on a protracted struggle. It would instantly remove all the vulnerability, embarrassment, and inherent weakness which result from slavery.

Since secession had occurred largely as a measure to protect the institution of slavery, it’s not surprising that there was pushback against Cleburne’s idea. Resistance to the measure was most cogently expressed by General Howell Cobb, who wrote in January 1865, “If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” Cobb was precisely correct, but not in the way he intended.

By early 1865, the Confederacy was in desperate straits, and did not have manpower to spare. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the Confederate Congress finally took steps to raise Black troops. Notably, the enslaved men who fought for the Confederacy were not guaranteed their freedom for their service. It was a moot point anyway, as Robert E. Lee would be forced to surrender within a month.

Indigenous People Fought On Both Sides In The Civil War

Native Americans were involved in the American Civil War, particularly in the West, an often-overlooked theater. Cherokee and Creek soldiers fought on both sides, which led to many family and intertribal conflicts.

Early in the war, Confederate authorities signed treaties with the Five Tribes, and had uncontested control of Indian territory. Most Cherokee people sided with the Confederacy, though some remained loyal to the Union. The Cherokee people had largely assimilated into mainstream society, and some even owned African American slaves. Stand Watie was a Confederate general, commander of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, and leader of the Cherokee Nation. His political rival, Cherokee leader John Ross, chose in the end to side with the Union; their personal conflict mirrored the deeper schism within Cherokee society during the war.

The Battle of Honey Springs, fought in Indian territory, is sometimes referred to as “the Gettysburg of the West,” as it was fought just two weeks after that famous engagement. The Union victory at Honey Springs capped the Federal invasion of the Indian territory and ended Confederate control of that region.

The Battle of Pea Ridge was a notable battle in which many Native Americans fought on both sides. Unfortunately, there are no sources written from the Indigenous perspective – only records written by white officers survive. This was the first major engagement between Cherokee Confederates and the Union Army.

It’s estimated that, all told, 20,000 Indigenous soldiers fought in the American Civil War. Some scholars suggest that Indigenous people were coerced into fighting “the white man’s war.” Another way to look at it is that Indigenous nations perceived the enormous impact of the struggle, and decided to get involved in a way that would give them some advantage, either collectively or as individuals. Some fought to protect the institution of slavery, while others fought for tribal sovereignty. One thing is certain – the Civil War brought to the forefront intertribal conflicts that had been brewing for decades.

The Indigenous Stockbridge Militia Fought With The Continental Army

The Continental Army enlisted Native Americans in New England into their forces during the American Revolution. The Indigenous peoples had to choose whether they would remain neutral or choose a side between the British and the colonists. The Iroquois Confederacy supported the British, while other groups supported the American colonies.

The Stockbridge Militia was made up of Indigenous warriors from Massachusetts. The main tribes that fought were the Mohican, Wappinger, and Munsee. The Mohican people acted as liaisons between the Continental Army and other Indigenous tribes in the area.

The Stockbridge Militia went through a few different phases. First, they trained themselves and offered their service to the colonials in 1774. At a meeting at the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, MA (hence their name), they pledged loyalty:

Wherever your armies go, there we will go; you shall always find us by your side; and if providence calls us to sacrifice our lives in the field of battle, we will fall where you fall, and lay our ones by yours. Nor shall peace ever be made between our nation and the Redcoats until our brothers – the White People – lead the way.

They were very skilled with rifles, bows and arrows, and hunting axes; their officers were also Indigenous. The militia fought in the Siege of Boston and the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga.

The second phase began when the Stockbridge Militia became incorporated into the 8th Massachusetts as the Stockbridge Regiment in 1777. In this way, their connection to the Continental Army was formalized. The regiment fought in the Battle of Saratoga and the Siege of Monmouth.

In August 1778, the Stockbridge Regiment lost the last Sachem (leader) of their tribe in battle. Many other soldiers were slain or wounded. George Washington disbanded the unit in September 1778 and gave the men $1,000 to split among themselves. They chose to return home and protect their families from the British soldiers and their allies.

After the war, the Stockbridge Militia was also active during Shays’ Rebellion, from 1786-87. They protected the town of Stockbridge from insurgents.

Black Soldiers Were Much More Involved In The American Revolution Than Most People Think

Black soldiers fought on both sides of the American Revolution. They fought for the side they believed would grant them freedom from enslavement – which, at the time, was practiced in all 13 colonies.

African American soldiers fought throughout the American Revolution, but are often overlooked in history. Crispus Attucks was one of the five men slain during the Boston Massacre. He is probably the most famous Black combatant of the conflict, but there were many others.

At the beginning of the revolution, free Black men were not allowed to fight, but this changed as Congress needed more manpower. Free Black men served alongside whites in the Continental Army for a short time, after which the Army divided into segregated units. Historians believe approximately 5,000-8,000 Black people fought on the colonial side, while as many as 20,000 fought for the British crown. A proclamation by Virginia’s royal governor, the Earl of Dunmore, that Black men who joined the British military would be emancipated, provided a powerful incentive for the latter group.

Many Black soldiers who fought in the American Revolution did not receive their freedom after their service was complete.

Nisei Soldiers Fought In WWII Despite Facing Internment At Home

Like African Americans, Japanese Americans encountered discrimination during WWII. This was especially prevalent after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Issei (first) and Nisei (second) generation of Japanese Americans faced intense scrutiny from American citizens. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which allowed for the internment of over 110,000 Japanese American citizens, on the pretext that they were potential enemy agents.

Japanese American citizens were removed from their communities and moved to internment camps – a brutal experience about which some Japanese Americans have written extensively. (For example, Monica Sone’s book Nisei Daughter describes what happened to her family before and during the internment.)

In spite of this injustice, Japanese American citizens still wanted to show their patriotism. The Nisei generation was eager to show their support for their country, but the military would not initially let them join.

Roosevelt allowed Japanese Americans to join the military in 1943, but they had to serve in a segregated unit – the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team. The motto of the 442nd was “Go for broke,” which meant that they would put everything on the line. The 442nd was made up of the following groups: the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, 232nd Combat Engineer Company, 206th Army Ground Forces Band, an antitank company, a cannon company, a service company, a medical detachment, and three infantry battalions.

Japanese Americans also fought in the 100th Infantry Battalion, which was activated in 1942 and was made up of 1,400 Nisei. The 100th was eventually integrated into the 442nd in 1944.

General George Marshall said of the 442nd:

They were superb! They showed rare courage and tremendous fighting spirit. Everybody wanted them.

Six decades after WWII, 20 men from the 442nd received the Medal of Honor. All told, over 10,000 Japanese Americans volunteered to fight for the United States in WWII. Serving in Italy, North Africa, and the Pacific Theater, they amply demonstrated their loyalty to the United States.

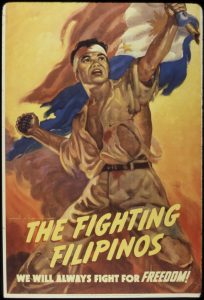

Filipino Americans Fought Tenaciously Against Japanese Occupiers In WWII

During WWII, Filipino soldiers fought in the US Armed Forces of the Far East (USAFFE) in four separate groups: the “Old” Philippine Scouts, Commonwealth Army of the Philippines, Recognized Guerrilla Forces, and New Philippine Scouts.

Many Filipino soldiers fought alongside American soldiers using guerilla tactics. It is estimated that 250,000 Filipino people fought, and more than 1 million perished, during WWII. Among other engagements, Filipino soldiers fought alongside American soldiers in the Battle of Bataan, the long-delaying action in early 1942 before Japanese forces drove out the Allies.

The Philippines was occupied by Japanese forces for a few years before the US military came back, fulfilling General Douglas MacArthur’s famous vow to return. Filipino guerilla fighters had been fighting throughout the Japanese occupation. President Roosevelt promised to establish an independent Philippines when the Japanese were removed. He kept his promise, and on July 4, 1946, the Philippines, became an independent country.

Filipino WWII veterans were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2017 for their service to the United States during the war.

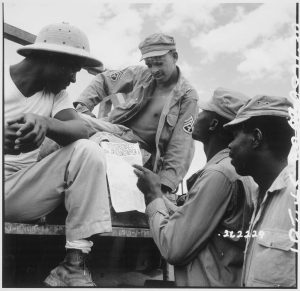

Black Soldiers Saw Combat In WWI But Returned Home To Discrimination

Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1917 to raise men for the war effort; all male citizens age 21-31 were required to register for the draft. Many African Americans had joined the war effort before the Selective Service Act as a way to prove their patriotism. African American servicemen were forced to serve in segregated units at the beginning of WWI. African American soldiers served in the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry.

One week after President Wilson declared the United States would be entering WWI, the military had to stop accepting African American volunteers because the quotas had been met. When the draft began, this policy was reversed, and many more Black citizens were called up to serve.

The Army was the least discriminative of all the branches. African Americans were not allowed to serve in the Marines and were given low positions in the Coast Guard and Navy. According to the National Museum of the United States Army, African Americans served in “cavalry, infantry, signal, medical, engineer, and artillery units, as well as serving as chaplains, surveyors, truck drivers, chemists, and intelligence officers” by the end of the conflict.

The 369th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the “Harlem Hellfighters,” was the first Black unit sent overseas during WWI. They had an impressive track record of never losing ground on the front line, and never had a soldier captured.

In 1917, the War Department created the 92nd and 93rd Divisions for combat missions. With the creation of segregated units, the military decided to create a separate training camp for African American officers. The camp was located in Des Moines, IA, and it’s estimated that 1,250 men went through the camp. The record shows that 250 of those men were already noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and the rest were civilians. In October 1917, 639 men were commissioned from the camp in Des Moines. It was closed shortly afterward, and African American soldiers were trained in other camps thereafter.

Black soldiers had embraced the name “Buffalo Soldier” by this time – in fact, the segregated 92nd Infantry Division’s unit patch illustrated a buffalo.

African American draftees were treated poorly, experiencing racism and hostility, and the discrimination was often overlooked by the War Department. Despite the poor treatment, African American soldiers worked tirelessly and performed essential duties toward the war effort. Upon returning home after the armistice, many encountered worse racism than before. In 1919, at least 10 veterans were victims of lynching. Black veterans were scapegoated as potential communist instigators during the Red Scare of 1919.

WWII Saw Black Soldiers Serving In Multiple Branches

African American soldiers served in many branches of the United States military during WWII, but they were fighting an internal and external battle. The African American community called this the “Double V” campaign: They wanted to end racism and discrimination abroad and at home. President Harry S. Truman formally desegregated the United States Army in 1948, making the Korean War the first conflict deploying a fully integrated Army.

Montford Point was a segregated training camp for African American Marines. It’s estimated that 20,000 Marines went through this camp, which was in operation from 1942-1949. Some have claimed the Marines at Montford Point went through a tougher boot camp than those at Parris Island.

The 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion was a segregated Army cavalry unit during WWII. Baseball legend Jackie Robinson was a member of this unit, which participated in the Battle of the Bulge.

The “Golden Thirteen” was the nickname given to the first commissioned and warrant officers to graduate from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, located in Illinois, in 1944.

-

During WWII, Thousands Of Black Women Served In The Women’s Army Corps And Other Organizations

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, led by Commander Charity Adams Earley, was made up of 855 African American women – 31 officers and 824 enlisted – whose job was to sort a two-year backlog of mail for US forces in Europe. Part of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), which was incorporated in 1943, they trained at Fort Oglethorpe, GA, and took as their motto “No mail, low morale.” Over 6,500 African American women served in the WAC overall.

The 6888th was the first all-Black unit sent overseas. Charity Adams was one of two African American women who were promoted to major during WWII. The 6888th worked around the clock in shifts, seven days a week, to sort over two years’ worth of mail.

African American women also served as Army nurses, in the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Services (WAVES) of the US Navy, and in the Coast Guard’s SPAR.

-

Navajo ‘Code Talkers’ Provided A Key Intelligence Edge In WWII

Native Americans proudly served in WWII. The most famous group was the Navajo (Diné) Code Talkers. At least 14 other Indigenous nations served during WWII, as well, including the Choctaw and Comanche. It was ironic that the US military asked the Native American people to speak in their original language, because the US government had been trying to eradicate Indigenous cultures for years.

First, the Army recruited Indigenous soldiers from Oklahoma in 1940. Soon, the Marines and Navy also employed Indigenous Code Talkers. Code Talkers were assigned to units in pairs: One soldier would go into the field and the other would remain behind to translate the messages.

Code Talkers transmitted intelligence in their native tongue, which was complex and indecipherable to the Japanese. Navajo was the only code that the Japanese never broke. Code Talkers had to memorize codewords because their language was largely spoken and not written down.

Over 500 Navajo served as Marines in WWII, and about 375-425 of these were trained Code Talkers. The Navajo worked tirelessly translating and communicating messages, and were involved in several important battles, including the D-Day invasion and the Battle of Iwo Jima.

Major Howard Connor said, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”